|

|

|

| Single Molecule Enzymatic Dynamics |

Real-Time Observations of Single Enzyme Turnovers

Essential to all life processes, enzymes are biological catalysts that accelerate biochemical reactions with high efficiency and high fidelity, unmatchable by artificial systems. The quest to understand how an enzyme works in real-time at the molecular level remains a central question. What can we learn from single-molecule experiments?

Our group was fortunate to be able to participate in the development of single-molecule imaging and spectroscopy at room temperature in early 1990s. The application of single-molecule imaging, spectroscopy, and manipulation has now lead to widespread research activities around the world because many compelling problems in biology can best be addressed with the single-molecule approach. Thanks to developments of in vitro assays by many groups, single-molecule enzymology has since brought mechanistic understanding of specific systems, as well as fundamental insights into enzymatic catalysis, even the prospect of human genome sequencing by the single-molecule approach

In 1998, we reported a real-time observation of enzymatic turnovers of a single molecule cholesterol oxidase, a flavoenzyme that catalyzes oxidation of cholesterol by oxygen [1] (Fig. 1A). The active site of the enzyme, flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD, Fig. 1B), is naturally fluorescent in its oxidized form but not in its reduced form. With excess amounts of cholesterol and oxygen, the emission from a single enzyme molecule confined in an agarose gel exhibits an on-off behavior (Fig. 1C), each on-off cycle corresponding to an enzymatic turnover. This time trace is not reproducible even though the statistical properties are reproducible. Stochastic behavior like this had been seen in single channel recording [2], but here we are were able to monitor chemical reactions of a single enzyme molecule taking place in real-time. |

|

Fig.1. (A) Enzymatic cycle of cholesterol oxidase, which catalyzes the oxidation of cholesterol by oxygen. The enzyme's naturally fluorescent FAD active site is first reduced by a cholesterol substrate molecule, generating a nonfluorescent FADH2, which is then oxidized by oxygen. (B) Structure of FAD, the active site of cholesterol oxidase. (C) A portion of the fluorescence intensity time trace of a single cholesterol oxidase molecule. Each on-off cycle of emission corresponds to an enzymatic turnover. (D) Distribution of emission on-times derived from (C). The solid line is the convolution of two exponential functions with rate constants k1 [S] = 2.9s-1 and k2 = 17s-1, reflecting the existence of an intermediate, ES, the enzyme-substrate complex, as shown in the kinetic scheme in the inset. From ref. 1. |

The Fluctuating Enzyme

The exponential rise and decay of the histogram of the waiting times indicate the existence of the enzyme-substrate complex (Fig.1D). By conducting other statistical analyses of the data, we found that a single enzyme molecule exhibits fluctuations of catalytic rates – a single enzyme molecule does not have a rate constant! This phenomenon, which had been hidden in the conventional experiments, turned out to be general. It is associated with conformational fluctuations (see next section).

Most ensemble enzymatic kinetics have been satisfactorily described by the classic Michaelis-Menten equation [3]. The Michaelis-Menten equation explicitly gives the hyperbolic dependence of the enzyme velocity v on substrate concentration [S] in an ensemble experiment, where KM = (k-1 + k2)/k1 is the Michaelis constant, [E]T = [E] + [ES] is the total enzyme concentration, and vmax is the maximum enzyme velocity. The observation of fluctuation occurring on multiple time scales raises an intriguing question: why does the Michaelis-Menten equation work so well despite the broad distributions and dynamic fluctuations at the single-molecule level?

Michaelis-Menten Equation Revisited

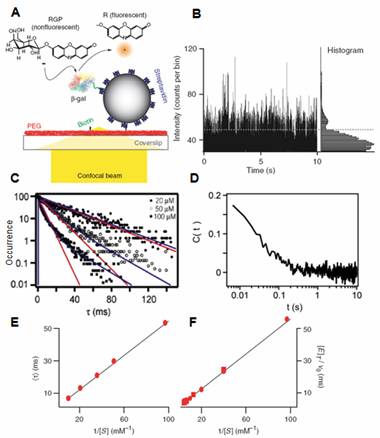

We conducted a single-molecule experiment on ß-galactosidase with a fluorogenic substrate that offers superb statistics (Fig. 2). This study allowed us to confirm the dispersed kinetics (Fig. 2C) and fluctuations of the catalytic rate at multiple time scales, from 10ms to 10s (Fig. 2D). Interestingly, despite the fluctuations, the Michaelis-Menten equation still holds on a single enzyme basis, except kcat and KM bear different microscopic interpretations, i.e. the weighted average of different conformers [4]. |

|

Fig. 2 (A) One ß-galactosidase enzyme molecule is linked to a streptavidin-coated polystyrene bead via a flexible PEG linker. The bead binds to the biotin - PEG surface of a cover slip. The hydrolysis of the photogenic substrate RGP is catalyzed by the enzyme, and the fluorescent product resorufin (R) is monitored in the diffraction-limited confocal volume. (B) A segment of the chronological waiting time trajectory as a function of time. (C) Histograms of the waiting time distributions at different substrate concentrations [S]. (D) Normalized autocorrelation functions of waiting times in the time trace in (B). This highlights the broad range of time scales of turnover rate fluctuations, spanning at least four decades from 10-3 to 10s. (E) Single-molecule Lineweaver - Burke plot of mean waiting times vs 1/[S]. (F) Ensemble averaged Lineweaver - Burke plot agrees well with (E), indicating that the Michaelis-Menten equation holds on a single-molecule basis despite the fluctuation. From ref. 4. |

This explains why the Michaelis-Menten equation works so well even in the presence of large fluctuations at a broad range of time scales. This intrinsic fluctuation is not significant for a system that comprises a large number of enzyme molecules, knowing the ensemble average result would be sufficient. However, if, in a living cell, there is only one or a few copies of a particular enzyme, such fluctuation might result in a large physiological effect.

It is important to stress that single-molecule enzyme turnover experiments are distinctly different from conventional in vitro enzymatic assays in that they are conducted under the nonequilibrium steady state condition with invariant substrate concentrations, which is usually the condition in a living cell [5]. We have recently developed a rate theory to describe how enzymes work under this condition [6].

References

- Lu HP, L Xun, XS Xie (1998 ) Science 282:1877.

- Sackman B, E Neher (1995) Single-Channel Recording. 2nd ed. Plenum (New York and London).

- Michaelis L, ML Menten (1913) Biochem. Z. 49:333.

- English B et al. (2006) Nat. Chem. Bio. 2:87.

- Min W, H Qian, XS Xie (2005) Nano Letters, 5:23773.

- Min W, XS Xie, B. Bagchi (2008) J. Phys. Chem. 112, 454.

|

|

|

|

|